[Note: If you go to a footnote, at the end of the footnote there will be a "back-link" character, '↵,' as a return link. Click on that and it will return you to where you came from -- no need to scroll back thru countless paragraphs. The back-link should work with screen readers too.]

[The target audience for this chapter, is descendants of my parents. Anyone is welcome to read it, but it may not interest the general public.]

MY MOTHER -- Jessica HOYT Thompson (1892 - 1983)

Manual Slideshow - Click on arrows

Writing about my mother always fills me with trepidation. I see her as complex, and don't feel I understood her as well as I did my father. Jessica (Hoyt) Thompson, was born in the small town of Nelson, PA, (near Corning, NY) in 1892. She was the eldest of three daughters of Joseph DeForest Hoyt and Frances Viola Goodrich, but was "the apple of her father's eye." And according to her mother, very spoiled as a result.

It was a small town, big enough to have a RR station, hotel, livery stable, two churches, a barber shop, post office and several small businesses, and served as a market place for the surrounding farms. Her great-grandparents were founders of the town, so she grew up in "one of the best families." Not wealthy, but active in he community and well respected. Her father was a farmer, who sometimes also operated a small store. Her maternal grandfather was the Methodist preacher and both her grandfathers were Civil War veterans and well respected. She was proud that she had multiple ancestors who were early settlers of the colonies, coming to MA, CT and New Amsterdam in the early 1600s. And very proud of being a DAR member. (My dad's ancestors were early settlers of New France, coming with Champlain.)

Perhaps because her family had been very involved in their community, we were brought up with a strong sense of community responsibility and civic engagement.

Her rather idyllic childhood came to an abrupt end at the age of 10, when the father she adored dropped dead at age 42. They lost the farm and she and her sisters and mother moved in with her maternal grandparents. But it was very cramped and four more mouths to feed was a strain on her retired grandparents income. As a result, mom and her sister, Betty, moved in with her father's sister, Inez (Hoyt) Boller and her husband, (my namesake), Billy Boller. Their two children had died very young, and they welcomed mom as if she was their child. Mom called Inez "Auntie." Inez was fond of all three of her nieces, but she and mom bonded. And Billy Boller was fond of her. My siblings and I had no living grandfathers and so we called him "Grampa Bill."

She grew up on the Boller's farm, which in Inez' day was called "Rose Lawn Farm," but was weather beaten and in need of paint by the time I started visiting. We spent much of the summer there. Before my time, Tom had an ill-tempered pony there, named "Betty." (I assume that was her name when Grampa Bill bought her rather than being named after my mother's sister.) My siblings all had fond memories of "Auntie," but she died soon after I was born, so I had no memories of her. Mom loved the Bollers' sheep farm. Most of his income came from selling the lambs to a slaughter house each fall, but of course he also sold wool. And had a side job of a "milk route." He would get up before dawn each day, leave with his old Reo stake bodied truck, and drive his assigned route, picking up the dairy farmers milk cans, taking them to a nearby condensary (a plant where raw milk was turned into condensed milk and canned). He would return the empty cans the next morning when he picked up that days milk.

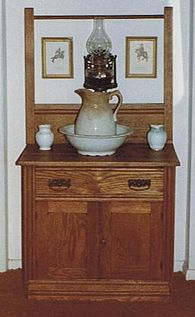

My visits there were invaluable for introducing me to what life

was like in the 1800s. It had no electricity, no indoor plumbing,

no central heating. On one side, in the yard next to the kitchen

door and side porch, was a hand pumped well. The outhouse was on

the opposite side of the house. Kerosene lamps provided the light

at night. A pot

bellied stove provided the only heat. And kettles placed on

top provided the hot water to pour in washtubs for Saturday night

baths. Each bedroom had a wash stand, with a large bowl and

pitcher for washing up in the morning. And a commode (cabinet to

hold a chamber pot). Crawling into a cold bed in an

unheated bedroom in winter was nothing to look forward to so

rectangular soap stones, with a handle, were heated on top of the

stove and then used as bed and foot warmers. It made you

appreciate modern conveniences. In summer, cooking was done on a

two burner kerosene, table top stove. I especially remember the

mattresses, which were stuffed with dried corn husks and made a

lot of noise when you rolled over. Getting up on a cold winter

morning, with the room temperature not much above freezing

inspired getting dressed under the covers, as much as was

practical. When I hear people waxing nostalgic about "the good old

days," I think of what daily life was really like then. And of all

the young children's graves in the cemetery. Lifespans then were

not too different from now -- for those who lived to adulthood.

Crawling into a cold bed in an

unheated bedroom in winter was nothing to look forward to so

rectangular soap stones, with a handle, were heated on top of the

stove and then used as bed and foot warmers. It made you

appreciate modern conveniences. In summer, cooking was done on a

two burner kerosene, table top stove. I especially remember the

mattresses, which were stuffed with dried corn husks and made a

lot of noise when you rolled over. Getting up on a cold winter

morning, with the room temperature not much above freezing

inspired getting dressed under the covers, as much as was

practical. When I hear people waxing nostalgic about "the good old

days," I think of what daily life was really like then. And of all

the young children's graves in the cemetery. Lifespans then were

not too different from now -- for those who lived to adulthood.

One consequence of growing up on that farm was that she never wanted to have lamb or mutton again, and never cooked it for a meal. But she loved that farm and the memories it held for her. Wm. Boller left it to her when he died. She kept it for several years, but couldn't get out very often and reluctantly sold it.

After graduating she went to Mansfield Normal School and lived in a dorm. At that time, two years at a normal school was born in the small town of was required for a certificate to teach primary grades (1 - 6) and a third year to teach secondary grades (7 - 12). Mom got her primary certification, taught for a year in Nelson, returned to Mansfield for her secondary school certification, and in 1916 married the handsome ex-sailor who'd courted her with the mandolin. (NYS recognized PA certification, so she was able to teach there.)

They first lived in West Winfield, NY and North Brookfield, but soon settled in the Binghamton area, where she usually taught is small, rural schools. Dad and his brother-in-law, Roy Walker, who lived nearby, enjoyed fishing in Nine Mile Swamp (as did their sons later).

Mom returned to Auntie's in Nelson for the birth of her first two children, "Tom" (Walter, Jr. in 1917) and Anne in 1919. (Her mother was living and working in Elmira, NY then. Hank was born in Binghamton in 1922. (I was an "afterthought" much later.)

Her sister Isabelle graduated from Mansfield Normal School and taught Phys Ed in the Elmira area. I think Isabelle and her mother lived together before her marriage, but after Isabelle married in 1925, gram lived with her and husband Tom Field. Isabelle was childless and wanted to adopt me, but mom declined, which may have been fortunate for me because Isabelle died 2 years later from meningitis. And gram came to live with us.

The Depression years were tough, with dad being unemployed or underemployed much of the time and Hank getting polio, but we survived (but moving often). WW2 brought relative prosperity, but mom gave up teaching when I was diagnosed with rheumatic fever.

She was active in the community, teaching Sunday School, holding 0 offices in the PTA and Presbyterian Women's Organization, the church choir (until she "lost her singing voice"), the somewhat prestigious Garden Club and and had been active in the Grange. She was active in several women's bridge clubs, painted and had great flower gardens. I always mistakenly thought she somehow managed to join the exclusive Monday Afternoon Club -- that's what the sign still read. But apparently they had gone out of existence and she just belonged to a group that met there (perhaps the Garden Club). I do know that she attended regularly, whatever the group's name was.

Her DAR membership meant a lot to her. I'm pleased that in 1939, when the DAR refused to let Marion Anderson use their concert hall, she, like Eleanor Roosevelt, resigned in protest.

In those days the country was awash in prejudice. The KKK openly held parades in most cities. Mayors and public officials often openly supported them. Racial stereotypes were ubiquitous: Rastus and Mandy jokes, black-face performers like Al Jolson and minstrel shows. A common expression was "There's a Ni**er in the woodpile." Brazil nuts were called "Ni**er toes." Kids blithely counted "Eeny meeny, miny moe, catch a ni**er by the toe."

So, in some ways she was very progressive for her times and happily supported Nelson Rockefeller. But she also believed in preserving our country's WASP (White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant) cultural traditions. Immigrants were welcome, but needed to be "Americanized" and assimilated to understand, appreciate, and embrace American values. And we, as descendants of the early colonists, had a special obligation to help "enlighten" the foreigners. The emphasis seemed to be on the benefits to them (and the country) of their adopting our values. As was typical for her generation, there seemed little awareness that their culture and traditions could enrich American culture and life. One story in particular illustrates the "mixed messages" of my childhood. The first African-American family (whom I'll call "The Smiths") was moving into our neighborhood. Some of the neighbors were very upset and wanted to oppose it, but mom was very supportive. However, her support, as I recall, was worded "I'd a lot rather have good Ni**ers like the Smiths as neighbors than Polacks like [those who] live next to me now." (BTW, the Smiths moved in and resided without incident, but were not invited to neighbors' picnics.)

She had cardiac issues all her life and in later years, severe rheumatoid arthritis (sometimes painting with brushes strapped to her hands) and later a series of stokes and dementia.

Their marriage wasn't conflict free, they often fought and even went through a trial separation in the early 1940s.

She was a worrier. Overprotective of me. Insisted on picked out my clothes almost until I graduated from college. Loving but inhibited and not demonstrative. She'd read a popular book on parenting that said you shouldn't pick up a crying child or you'd spoil them and felt duty bound to stifle her "maternal instincts." I don't recall either parent ever saying "I love you" or once I reached school age, ever hugging me.

And I see her as "meddling" in her children's lives. I've already mentioned her opposition to my marrying Rachel or Dottie. And I believe she campaigned against my brothers "getting involved with" Rachel's sisters. And to my sister's first marriage. But she'd also weighed in against her earlier suitors. And was adamant when my brother considered divorce to protect his kids from abuse. In part that was practical -- "No court is going to grant custody to the father." (Which was probably true then.) But also as a matter of reputation -- "Divorce isn't what we do." She and I had a showdown about her countermanding my orders to my kids. "It's a grandmother's prerogative to spoil her grandchildren if she wants to." (I won that one.)

She had some great recipes (most of which were closely guarded secrets). Her usual cuisine was traditional New England. Meat wasn't done if it hadn't fallen off the bone yet. But she was a skilled baker. Huckleberry tea cakes were her crème de la crème. But she made great cream puffs, eclairs and popovers. (I make good popovers too, but from a recipe on the flour box.) And she made very good pies -- her chocolate pies especially are fondly remembered (but all her pies were good).

She was extremely hospitable. Family friends who lived alone were always invited to our holiday meals. And anyone present as mealtime approached would be invited to stay to dinner even if that required a miracle of loaves and fishes to stretch what she had planned to serve in order to accommodate one more. She, and my sister both denied they took it seriously, but both liked to read guests tea leaves. I recall many occasions in which my mother would begin doing a reading -- then suddenly become disturbed at what she saw, her facial expression would markedly change and she would quickly break off the reading, making some excuse such as the leaves had become rearranged. But they both believed they had "powers." My sister also read palms. One supernatural incident in particular comes to mind. They both were certain that at the moment Tom was injured they both woke up from frightening dreams and "knew" that something awful had happened. Of course it was weeks before they actually knew the details of when he was injured. A telegram did soon come from the War Department informing my parents that he had been injured and was in a hospital, but the specifics of what day and hour didn't come out until much later.

Her sense of humor was very different from my father's and seemed that of the Victorian Age. She loved saying things like "You scream; I scream; we all scream for ice cream." And "Railroad crossing, look out for the cars. Can you spell it without any R's?" Or "Beach, birch and maple, all begins with 'A.'"

She especially liked to draw the following story, which you were invited to read aloud:

A B C D?

L M NO

S M R

C M ?

See footnote for the "correct" answer. If the "solution" seems pretty dumb, perhaps that proves that you're not a Victorian :)

If you're up for one more sample of Victorian humor and their proclivity to euphemisms, see.

One of the scars that I think the Victorian mindset inflicted on families was the tradition that family skeletons must be hidden away in well locked closets. Put out of sight and out of mind. Some of this may be tied in with a sense of shame and fear of damaging the family's reputation in the community. But these things are all part of life. And everyone's family has experienced one or more of them. A relative committed a crime or was raped. (My Uncle Maurice [pronounced 'Morris'] accidentally killed a neighbor.) Or had a child out of wedlock. Or had mental illness. Or was addicted to alcohol, drugs, gambling or whatever. My father wouldn't talk about his Uncle Kearney [pronounced 'Carney'] -- didn't even want his name spoken in the house -- I don't know why, nor did any of Kearney's grandchildren have a clue what that was all about. All he's say was "Kearney's a bum. Don't be like Kearney."

Not in connection to Kearney I've read in the papers about one adulterous cousin who was involved in a ménage à trois that resulted in a trial and newspapers' field day. The rational given for secrecy is often to protect children, but as Lemony Snicket and Margaret Holmes have shown, that may not always be the best way to protect children.

Both of my parents enjoyed antiques. They would shop at dealers and flea markets, buy pieces they liked. Dad would refinish them if needed. If chair seats needed re-caning or their splint or reed seats replaced, they would usually pay to have that done. If the piece didn't have beautiful wood, dad would often paint it black and mom would stencil it, often in guild. Sometimes the refinishing would remove some patina and decrease the piece' value as an antique, but the result was always a handsome piece of furniture. Mom collected cranberry glass and Sandwich glass