CAMPBELLs, LUGGs, & BLACKWELLs of Nelson, PA

Bill Thompson's Memoir

Chapter 7 - My Brother, Walter F. "Tom" Thompson, Jr.

[Note: If you go to a footnote, at the end of the footnote there will be a "back-link" character, '↵,' as a return link. Click on that and it will return you to where you came from -- no need to scroll back thru countless paragraphs. The back-link should work with screen readers too.]

[The target audience for this chapter, is descendants of my parents. Anyone is welcome to read it, but it may not interest the general public.]

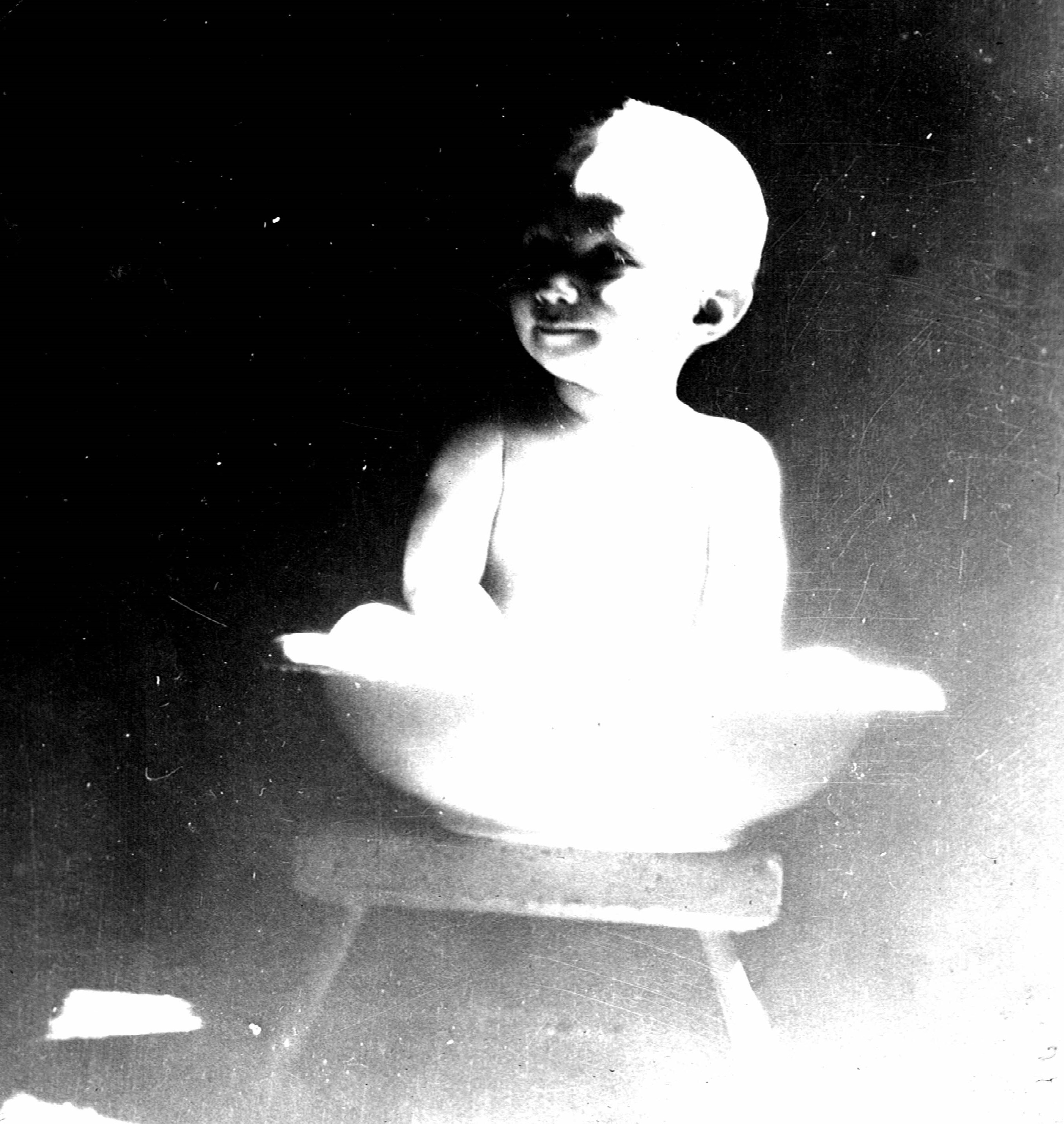

MY BROTHER -- Walter F. Thompson, Jr. (1917 - 1993)

My Role Model

Manual Slideshow - Click on arrows

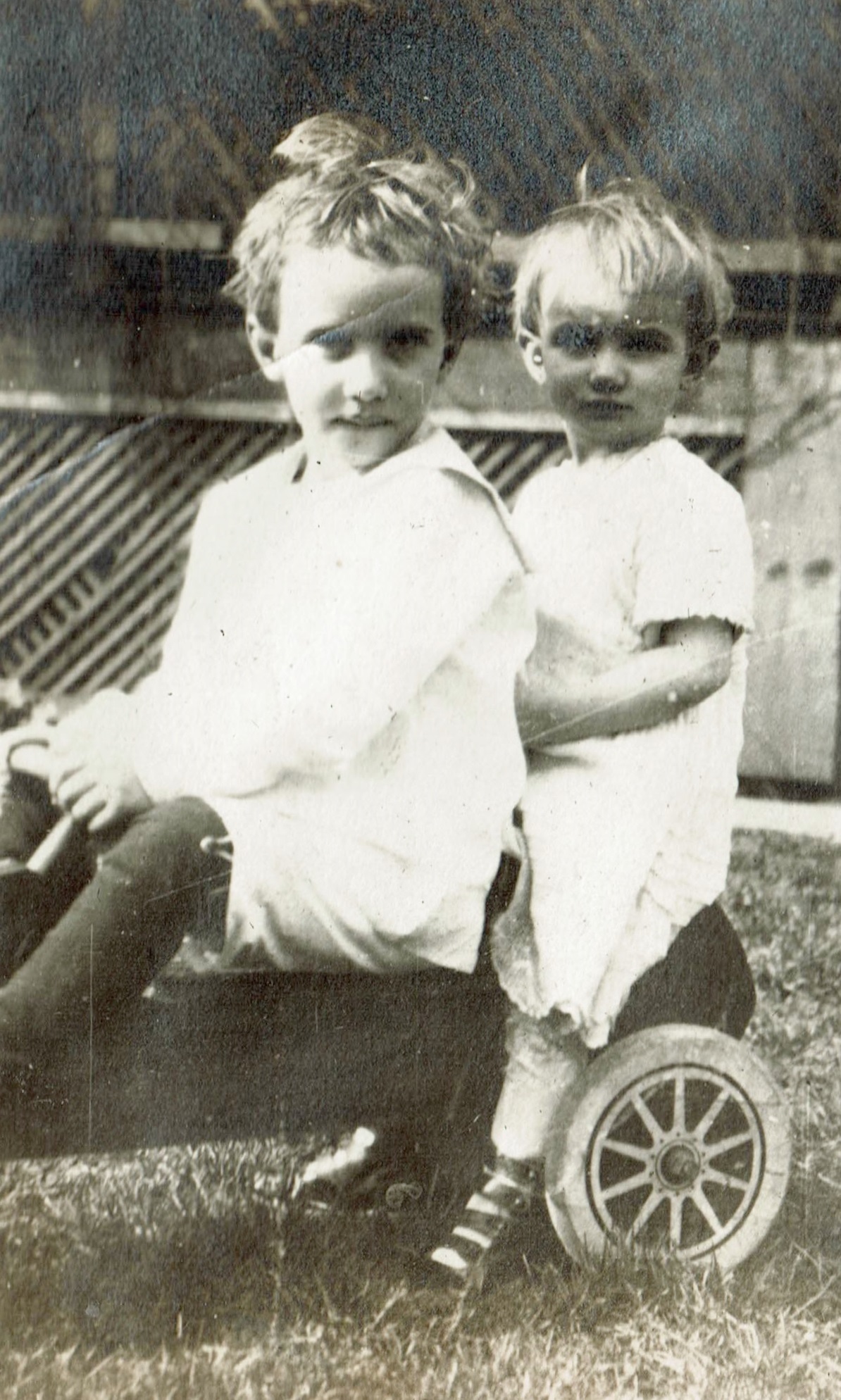

My eldest brother was my hero. He was kind and considerate to me. (I already mentioned his taking me for walks in his Adirondak pack-basket when I was a toddler.) I can't count all the things he introduced me to: puns, camping, poetry, Tolkien, folk music, how to identify sassafras and when to harvest it, and countless more. I couldn't wait till I was old enough to follow in his Adirondack paddling and hiking "footsteps." I was "Billy" to everyone else, but he always referred to me as "Willie" when I was a kid. He enlisted in the Army when I was a first grader, but always sent me things which I cherished -- rattlesnake rattles from the Mohave desert. A Navajo thunder-bird ring. Sea shells from the Pacific, etc. His letters home included "Tell Willie ..."

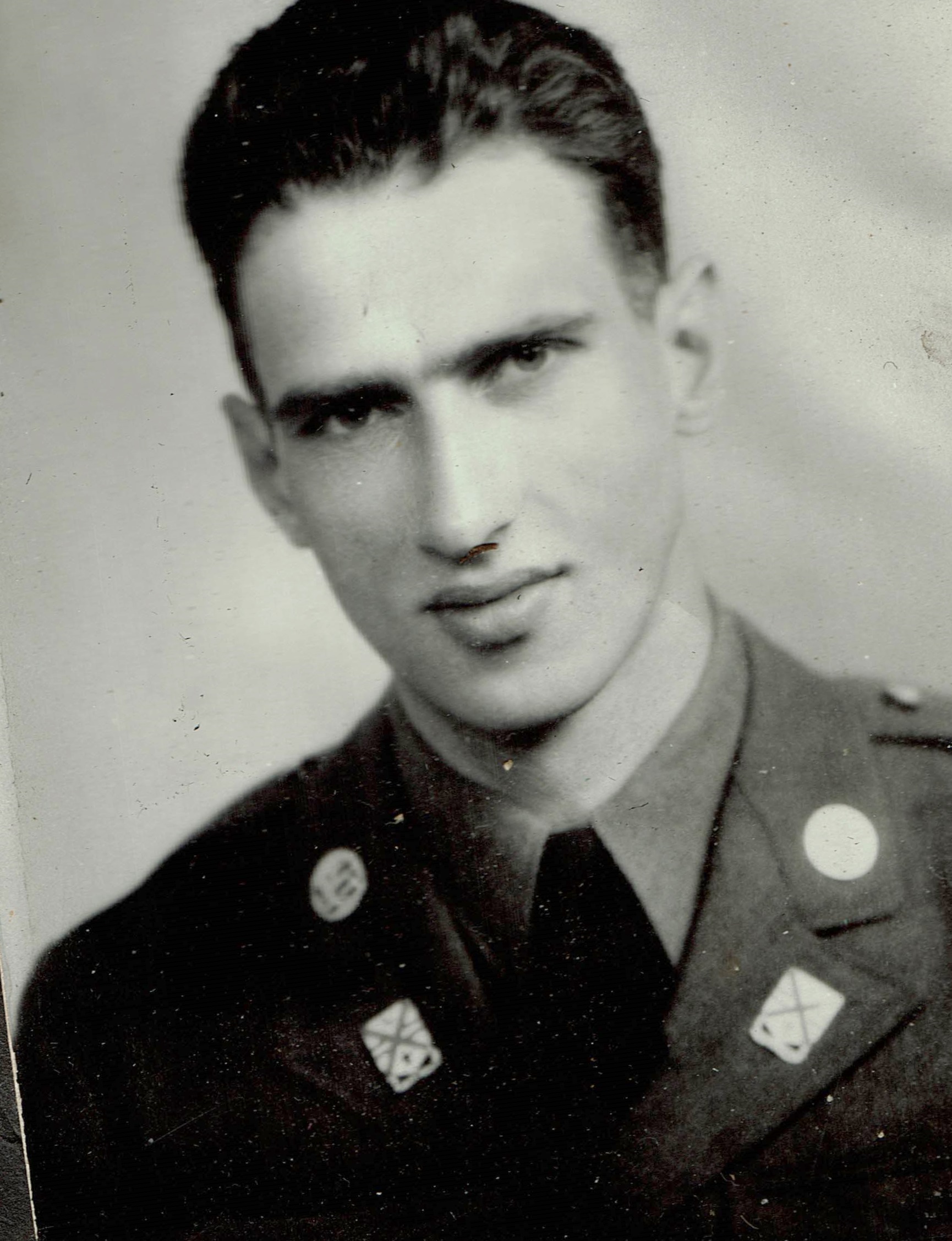

He was superbly trained by the army. They sent him to the Mojave Desert to train for North Africa, but by the time he was finished they didn't need him in Africa anymore, so they sent him to Mt. Rainier, to train for fighting in Italy's Appenine Mts. But by the time he graduated from that training they decided they needed him in the Pacific, and sent him to Hawaii for more training. Because he was taller than average, he was assigned to carrying a BAR (a light machine gun usually fired prone supported by a bipod (a two legged support), but carried via a shoulder strap and capable of firing from the hip as you walked. He first saw action in Papua New Guinea, where he came to know and like a village of head hunters. "They're nice fellows as long as you stay on their good side." The Japanese committed atrocities and hadn't stayed on their good side, so the locals were glad to help guide the GIs.

After that fighting was over, he was sent to northern Australia for R&R, and then to Mindanao, for more combat. And finally to Luzon, where his mountaineering training was put to use as the allies moved toward Baguio. His unit held a ridge in the mountains, protecting an Army Engineering crew building a road to Baguio for the advancing army. After weeks of being ahead of their supplies and having to live off of rice taken from the knapsacks of Japanese soldiers they'd killed, his company came under an intense artillery barrage and suffered 70% casualties in a half an hour. He had survivors' guilt because he saw his best buddy disintegrate from an exploding shell. Tom was badly wounded, losing the use of one lung and carrying countless pieces of shrapnel (they would work their way out for decades). But he was sure that he would not have survived had his buddy, who was between Tom and the explosion, not absorbed the worst of the blast. While in a field hospital for months, he contracted malaria, which would flare up repeatedly over the next several years.

To understand Tom, you need to know that he turned down repeated attempts to promotion to sergeant and remained a corporal. "I didn't want to order men to their death." Eventually he was moved to hospitals in San Francisco and DC, before recovering enough to be discharged. After getting his Purple Heart and other medals, he was offered disability, but declined. "I can still work."

But like every combat veteran from WW2, Korea and Vietnam that I've known, he suffered from PTSD for the rest of his life. (In WW1 they called it "shell shock" and "battle fatigue" in WW2. But "real men" were supposed to be able to tough it out and not need help. Of course back then it wasn't well understood and the meager help available often wasn't much help.)

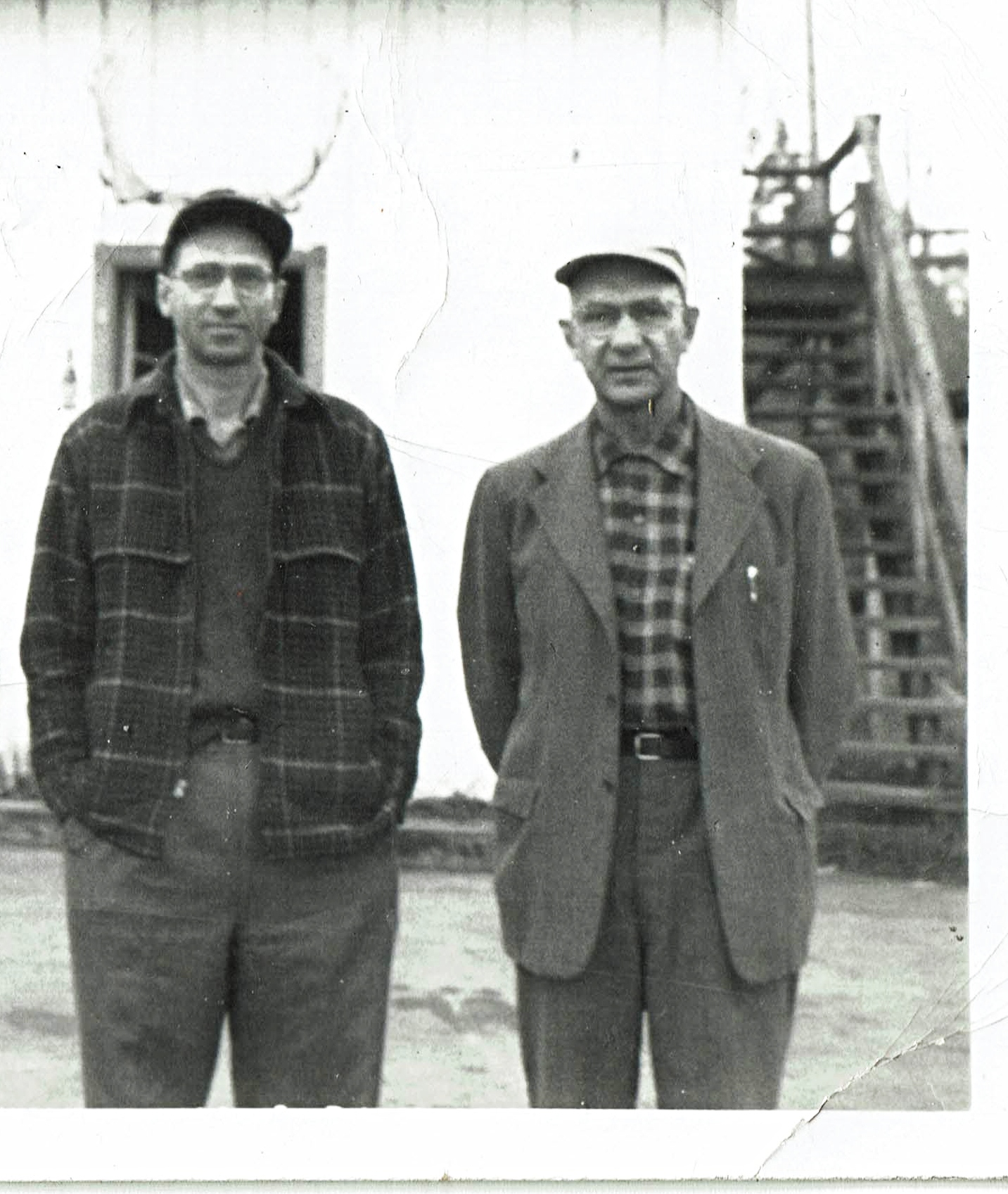

Before he enlisted, he's met Anna Gretna Walker, sister of a close friend of his. Additionally, she was a friend and coworker of my sister. He and Gretna corresponded through is army years and married as soon as he was well enough. He went to Triple Cities College in Binghamton on the GI Bill (one of the best investments the US government has ever made) and got a BA in botany. Then, loving history, he attended the NYS College for Teachers in Albany, for an MS to teach HS history. But, discovering he didn't like his student teaching experience, upon graduation, took a job as an electronics technician at Link Aviation, where my father worked. He later transferred to their "Contracts" department where he negotiated with NASA and the DOD about contract specification details. (I didn't come on my versatility and ability to take on jobs with zero experience by pure chance.) I didn't get to see him much during his college years, he was pretty busy. But we always felt "connected."

The second major trauma in his life was the death of twin sons when they were only a couple of days old. He wouldn't consider counseling and I think he was deeply scarred the rest of his life. He would visibly flinch when he encountered boys the age they would have been. And for a long time avoided my sons. Mom tried to encourage him and Gret to adopt, but he refused to consider it. He came back from the war still believing in God, but couldn't forgive him for allowing the carnage of WW2. He never again went in a church, except for weddings and funerals.

For a while he had a cabin cruiser, based near Ithaca. But he spent many hours canoeing and many more in boats on lakes and rivers of all sizes, which is why he probably developed a melanoma on a leg that wasn't discovered until it had metastasized. That was in the days before the ACA when insurance companies controlled most of the health care calls, and while he was getting radiation treatment for his cancer, his insurance company announced, "Sorry, you've reached your lifetime cap, no more health insurance coverage for you.

Speaking of funerals, there's a "small world" story about his funeral. After he was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer, a neighbor asked permission to tell the pastor of his nearby church. The pastor, whose church was just a few blocks away, on the same street, did visit. He was from the Philippines. At the time Tom was wounded, the pastor was a boy, hiding in the jungle, a few miles from Baguio, so they had a lot to talk about. The visits continued and they became friends. That pastor was invited to do a scripture reading at Tom's funeral. His presence was a big surprise to Tom's nephew's wife. He had been her youth pastor when growing up in Clarke Summit, PA. "It's a small world after all."

Tom was multi-faceted. He was an excellent photographer, especially of blossoms. He had a sharpshooter medal from the army and participated in many target shooting meets, I think becoming a NYS champion. He was a talented wood carver. He hunted, fished, hiked, and canoed. He liked minerals, picking up specimens of semi-precious gemstones such as garnets and many "Herkimer diamonds." He filled 3 walls of his basement with a model train layout with bridges and tunnels that accommodated several trains simultaneously. He spent countless hours building RR cars for the trains, buildings, trees, shrubs, etc. He was very active in the Masons, both in his local lodge, but also statewide, popular because he had memorized so many of their rituals that had to be recited at various ceremonies. He would delve deeply into a hobby for several years, then put it aside and move on to new territory. He had a fine collection of antique glass and continued adding to that.

Fishing remained a constant. He and Hank both went through periods of serious creators of trout flies and Hank made larger pieces, such as a "mouse" lure for bass. Dad and Hank continued to be avid trout fishermen, but all also did boat fishing for bass and Northern pike. Dad also liked to catch perch for eating. Both Dad and Tom would fly to remote areas in Quebec and northern Ontario in one of Link's planes and company pilots, a free benefit offered "old hands."

I live just south of the Poconos (they're more like hills than mountains, but mountain laurel country). He loved photographing them (and dogwood blossoms), so each spring, when I saw that they were blooming, I would give him a "heads-up" phone call. For years after he died, when I would see their blossoms come out I would automatically think "I've got to alert Tom" -- and then feel sad when I remembered there was no need to call him. When he was a botany major, he impressed his professors with photographs he took through a microscope of single celled plants and had a talent for dyeing portions of a cell to provide better contrast. In later years he often used high magnification camera lenses to shoot tiny blossoms, barely visible to the naked eye, or close ups of lichens. For years he had his own darkroom where he developed and printed his photographs. I still have albums of his Adirondak hiking and canoe trips. And a small hard bound book he used when writing poems, short stories or verbal sketches. He liked capturing legends of Navajo and Pacific Islanders.

When it became clear that he only had weeks left to live, I wrote him a letter, outlining how much he'd meant to me. I'm very glad I did that -- it meant a lot to him. When it became clear that he only had days left, I went up to Binghamton for a final visit -- staying at my sister's apartment. There already were blizzard warnings before I left her apartment to go to his home to say goodbye. I had the car radio on and when I was less than halfway there I heard the announcement that the sheriff had declared a state of emergency and closed the roads. I figured that it was now or never -- that if I turned around he'd be dead before the roads were reopened, and so I pressed on. Mine was the only car on the road. Main St. in Johnson City was NY17C -- two lanes each direction, with two lanes for parking. It was hard to see because it was snowing so hard. So I drove down the middle of the street (blinkers on), with the driver's window open so that I could scrape the windshield with one hand as I drove. Somehow I made it to his house and we said our goodbyes. I was glad I'd come, but the return trip to my sister's was some of the most challenging I'd ever done -- what with how hard it was snowing and how much had accumulated. But I'd grown up driving in NYS winter conditions, and made it back to my sister's OK and without being arrested. (I was always prepared for getting stuck in the snow. I had a sleeping bag in the car, so I wouldn't freeze. A shovel to dig out of a drift. Reflectors and flares to set out to reduce the chances of being hit. Etc.) He died the next day. It was 3 days before the state of emergency was lifted, so if I had turned around there would not have been another opportunity.